Quick, think back to the last true crime mystery that you

watched or read about. Maybe it was Serial

or Making a Murderer or whatever you

happened to see on Investigative Discovery last night or maybe even The People v. O.J. Simpson. Do you

remember the name of the killer (or accused killer)? So long as the story is

still fresh in your mind, I’m betting the likes of Adnan Syed or Steven Avery or

O.J. Simpson are in your head. Now next question – do you remember the names of

the victims?

Sometimes victims become as unintentionally famous as the

people who killed them. Most times they fade into obscurity, unless they become

part of the zeitgeist like Nicole Brown Simpson or Hae Min Lee. But whenever we

watch movies about them or read stories or listen to podcasts, we almost always

lose sight of the victims because we tend to get the story more or less from

the perspective of the killer, accused or otherwise. There’s a practical reason

for this, of course – dead people are notoriously hard to get on the record

whereas accused or convicted killers can be interviewed. That dynamic creates a skewed view on crime

where the victims become cyphers, unable to give us the answers we really want.

So what if you had a crime story where the victim of the

murder could still speak? Answer that question, and you’ve got Netflix’s new

documentary series The Keepers. The

series examines the murder of Sister Cathy Cesnik, a nun and Catholic high

school teacher in Baltimore in 1969. And before you get too checked out, this

is not a story about ghosts or mediums or mistaken identity or any other trickery.

It is, however, about how the victims of a murder (mostly) survived.

|

| Catholicism, man. Amirite? |

A quick note: It’s hard to have traditional spoilers in a

true crime story, especially one that officially remains unsolved. But The Keepers takes viewers on such an

intense ride that if you prefer to experience the story with all the emotional

twists and turns that the series intends you to experience, you may want to

stop here and go watch the first three episodes before reading any further. The

series is full of revelations and I’m only going to review a few of them

briefly, but if that’s a concern for you consider this your spoiler warning.

Now that that’s taken care of, let’s explore the facts of

the case. In 1969, Sister Cathy Cesnik was a 26-year-old nun living in Baltimore

and working as a teacher. Not that much older than the girls she taught, she

was popular and well-liked. Several of her students, now women in mostly their

late 60s, recount how close they felt to her and inspired by her they were.

Sister Cathy began her teaching at Archbishop Keough High

School, an exclusive all-girls Catholic school. She taught English and Drama

for several years, but despite a strong tenure at Keough, Sister Cathy

nonetheless left the school at the end of the 1968-1969 school year and took a

position at a local public school with another young nun in her order. The two

nuns even opted to live together in an apartment in West Baltimore. The move

was part of an experiment in which nuns would try to live among the world

rather than in cloistered lives.

On the evening of November 7, 1969, Sister Cathy left the

shared apartment and drove in her car a short distance to a shopping center to

buy an engagement present for her sister in Pennsylvania. Along the way, she

cashed a paycheck and stopped off at a local bakery. She left around 8:00pm. When

she hadn’t returned home around midnight, her roommate Sister Russell called a priest

and mutual friend, Rev. Koob who drove to the women’s apartment. At 4:30am, Rev.

Koob discovered Sister Cathy’s car parked illegally less than 100 yards from

the apartment building. The car was dirty and had twigs and debris inside. (In

a weird coincidence, Sister Cathy’s apartment was located near the spot where

Hae Min Lee’s body would be found 30 years later. Stay classy, Baltimore.)

Baltimore Policy conducted a basic search, however they reportedly

didn’t see any evidence of foul play or violence. Sister Cathy would be

officially missing for almost two months until on January 3 when two hunters

discovered her partially-clothed body in remote wooded area not far from her

home. An autopsy revealed that she had likely died due to a skull fracture

caused by a blunt instrument to the back of her head.

From there, the case went cold. It remained largely

inactive for almost 25 years when something happened that began to shed new

light.

|

| Enter these two jerks |

In 1994, a woman in her 40s came forward to say that she

had attended school at Archbishop Keough during the late 1960s. She alleged

that for three years, from her sophomore year until graduation, she was

routinely, systematically, and sometimes violently raped by a member of

Archbishop Keough’s staff, Father Joseph Maskell, who served as the school’s

counselor. The woman recalled detailed events where Father Maskell would call

her into his private office, demean her as a “whore” and a “slut” and then rape

her, telling her that only by having sex with him could her soul find

forgiveness. What’s more, he routinely arranged for her to be raped by multiple

men at the same time, often in his office with the door locked while he

watched. Some of these men, the woman later learned, were high-ranking city and

police officials.

While the woman’s reports were shocking, what really

grabbed public attention was another detail: the woman claimed that not only

had Sister Cathy known something about these attacks, but that Father Maskell

had taken the woman to see Sister Cathy’s dead body a few days after the nun

went missing. And what’s more, she may not have been the only one exposed to

all this; there could be others.

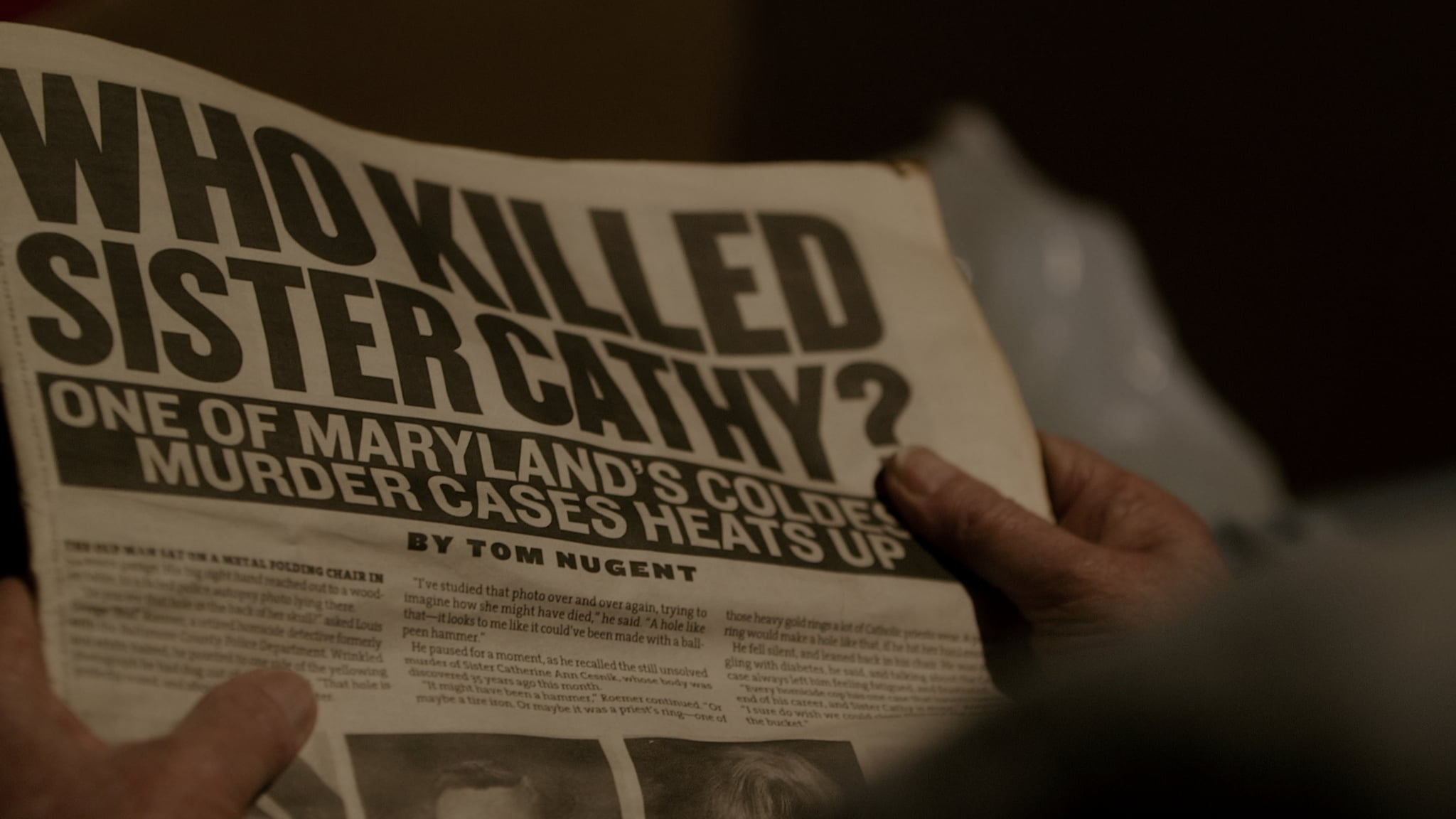

|

| Tom Nugent (no relation to Ted), reporter, shows the headline of his 90s era article re-opening the case |

And therein lies the detail that separates The Keepers from other true crime series

that I’ve seen. Unlike most that focus on the accused, The Keepers has access to the victims and investigates the events

surrounding Sister Cathy’s murder and Father Maskell’s alleged conspiracy and

sexual assaults through the eyes of people who were witnesses to them because

it was happening to them too. Sister Cathy is a victim, to be sure, but the

story quickly grows to encompass a number of victims who have spent more than

40 years unable to tell their own stories.

The Keepers is

dense, but immensely watchable. As I binge-watched it with a friend, I turned

to her after one episode and said out loud, “How are there four more episodes

to go? There’s so much information here; how are they going to keep shedding

new light on this story?” And yet, with each episode, the creators do.

This is largely thanks to the access they have not only

to the still living victims of the crimes committed at Keough High School, but

also thanks to the small sorority of women who, nearly 50 years later, are

still dedicated to getting to the bottom of the murder of a teacher they loved

and respected so much. What this means is that the narrative of the series is

almost entirely told through the voices of women, most of them middle-aged or

older. The women in this story have been abused, literally and figuratively, by

a variety of forces and personages and they’re only now getting to tell their

stories. That makes The Keepers a

natural expression of the nascent “Nevertheless, She Persisted” notion.

|

| Abbie (r) and Gemma (l), the amateur investigators still trying to piece together the crimes. AKA #Heroes. |

As such, the series gives out a measure of justice, but justice

is like Schrodinger’s cat – it both exists and doesn’t exist at the same time.

These women finally get to tell their stories and be believed, but of course

many of the perpetrators of the crimes done to them are long dead, having

escaped whatever worldly justice the law could have meted out to them. There’s

a sense throughout the series that history has already passed much of this story

by, making it even harder to gain any sense of closure about these events. In a

timely, though unrelated event, Keough high school, now officially named Seton

Keough High School, announced last fall that the

school would be closing its doors for good once school lets out this

summer.

Crime and punishment are almost always, by their nature,

reactionary things. It’s in keeping then that the way we’ve talked about both

of those things has been reactionary as well. The Keepers represents an attempt to change that narrative, if only

by looking at those concepts from a different perspective. The results are

fascinating to watch.

No comments:

Post a Comment